As soon as a system grows beyond a single machine, engineering stops being only about writing correct code and starts becoming about managing uncertainty. Distributed systems exist to solve problems of scale, availability, and performance, but they introduce an entirely new class of complexity. This is why distributed systems principles sit at the core of modern System Design interviews.

Interviewers are not looking for candidates who can memorize architectures or name tools. They are evaluating whether you understand the foundational principles that guide decisions in real-world distributed systems. These principles explain why systems behave the way they do under failure, load, and growth, and they shape every meaningful design trade-off.

This blog walks through the most important distributed systems principles from a System Design interview perspective. The goal is not to turn you into a theoretician, but to help you reason clearly, communicate confidently, and design systems that reflect real-world constraints.

Why Distributed Systems Principles Matter In Interviews

System Design interviews are structured conversations, not exams. Interviewers expect candidates to reason aloud, justify decisions, and adapt designs as constraints change. Distributed systems principles act as mental guardrails during this process.

When you understand these principles, your answers sound grounded instead of speculative. You naturally discuss trade-offs, anticipate failure scenarios, and avoid unrealistic assumptions. Candidates who lack this foundation often design systems that look clean on a whiteboard but fall apart the moment traffic spikes or a node fails.

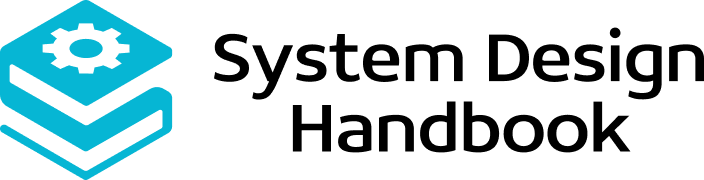

The Principle Of No Shared Global State

One of the most fundamental System Design principles for distributed systems is that there is no shared global state. Each node operates independently with its own local memory and view of the system.

This principle explains why coordination is hard. When nodes cannot instantly see the same state, disagreements arise about data values, leadership, and progress. In interviews, this principle often surfaces when discussing caching, replication, or service discovery.

Candidates who assume that all components always have an up-to-date, consistent view of the system quickly run into contradictions during follow-up questions.

The Principle Of Unreliable Communication

Distributed systems operate over networks, and networks are inherently unreliable. Messages can be delayed, duplicated, delivered out of order, or dropped entirely.

This principle forces engineers to design systems that do not depend on perfect communication. Timeouts, retries, idempotency, and failure detection mechanisms exist because the network cannot be trusted.

In System Design interviews, interviewers often test this principle indirectly by asking what happens when a service does not respond or responds slowly. Candidates who explicitly acknowledge network unreliability demonstrate a strong distributed systems mindset.

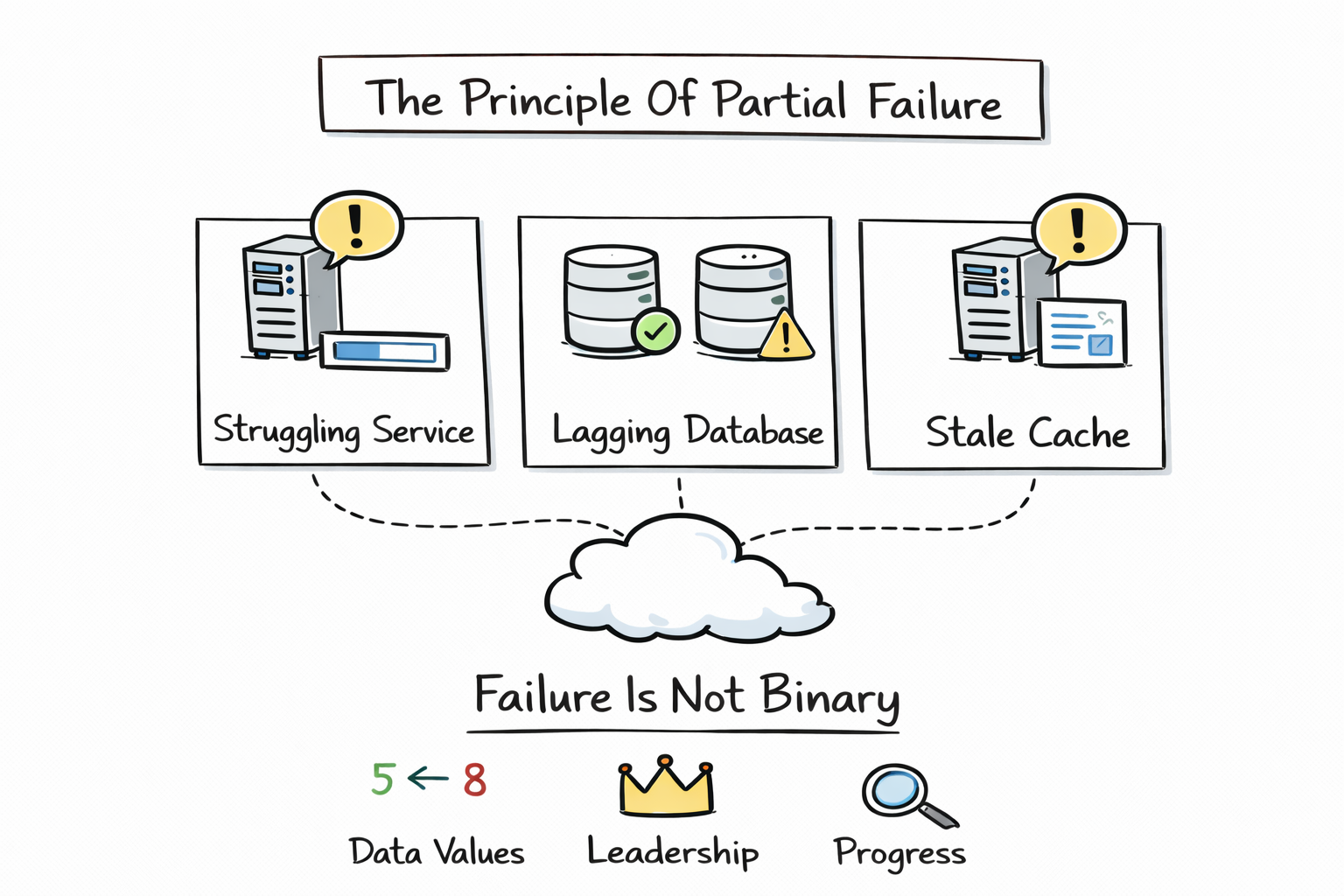

The Principle Of Partial Failure

In a distributed system, failure is not binary. Some components may be healthy while others are degraded or unreachable. This is known as partial failure and is one of the most counterintuitive distributed systems principles.

A service might accept requests but respond slowly. A database replica might be alive but behind on updates. A cache might return stale data rather than failing outright. These ambiguous states are common in real systems.

Interviewers favor candidates who design for these scenarios instead of assuming that failures are clean and obvious.

The Principle Of Decentralization

Distributed systems avoid centralized control whenever possible. Responsibility is spread across multiple nodes to improve scalability and fault tolerance.

Decentralization removes single points of failure but introduces coordination challenges. Leader election, consensus, and configuration management exist to balance decentralization with the need for order.

In interviews, this principle appears when candidates are asked how services discover each other, how configuration changes propagate, or how leadership is managed during failures.

The Principle Of Trade-Offs Over Perfection

One of the most important distributed systems principles is that no system can optimize everything at once. Improving one property often degrades another.

Latency, throughput, availability, consistency, and cost constantly pull designs in different directions. Strong engineers recognize this and make deliberate trade-offs rather than searching for ideal solutions.

Interviewers evaluate whether candidates can articulate these trade-offs clearly instead of presenting designs as universally optimal.

The table below illustrates common trade-offs that arise in System Design discussions.

| Design Focus | What Improves | What Becomes Harder |

| Strong consistency | Predictable reads | Higher latency |

| High availability | Fewer user-visible failures | Stale data |

| Low latency | Faster responses | Reduced durability |

| Horizontal scaling | Increased capacity | Coordination complexity |

The CAP Theorem As A Guiding Principle

The CAP theorem is one of the most widely discussed distributed systems principles, but its real value lies in how it guides design decisions.

The theorem states that during a network partition, a system must choose between consistency and availability. Because partitions are unavoidable, this choice is not theoretical; it is practical.

In interviews, candidates should not recite the CAP theorem but apply it. Explaining whether a system favors availability or consistency, and why, demonstrates real understanding.

The Principle Of Eventual Consistency

Eventual consistency is a direct consequence of operating at scale. Many distributed systems accept temporary inconsistency in exchange for availability and performance.

This principle requires application-level tolerance for delayed updates and conflicting views. Systems must converge toward correctness over time rather than enforcing immediate agreement.

Interviewers often test this principle by asking how systems behave during replication lag or how users experience stale data.

The Principle Of Horizontal Scalability

Distributed systems are designed to scale horizontally by adding more nodes rather than vertically by upgrading individual machines.

Horizontal scalability enables systems to grow incrementally and handle unpredictable traffic patterns. However, it introduces challenges related to data partitioning, load balancing, and coordination.

In interviews, candidates who naturally design stateless services and scalable data stores signal strong alignment with this principle.

The Principle Of Fault Isolation

Fault isolation ensures that failures in one part of the system do not cascade and bring down unrelated components.

This principle influences architectural decisions such as service boundaries, timeouts, circuit breakers, and bulkheads. By isolating faults, systems degrade gracefully instead of collapsing entirely.

Interviewers often probe fault isolation by asking what happens when a downstream dependency becomes slow or unavailable.

The Principle Of Observability

A distributed system that cannot be observed cannot be reliably operated. Observability is a foundational principle that enables debugging, optimization, and incident response.

Metrics reveal system health, logs provide detailed context, and traces show how requests flow across services. Without these signals, diagnosing distributed failures becomes guesswork.

Candidates who explicitly mention observability during interviews demonstrate operational maturity that many overlook.

The Principle Of Idempotency

Because messages can be duplicated or retried, operations in distributed systems should be idempotent whenever possible. Idempotency ensures that repeating the same operation does not produce unintended side effects.

This principle is especially important in payment systems, order processing, and event-driven architectures.

Interviewers often explore idempotency when discussing retries, failures, or exactly-once semantics.

The Principle Of Loose Coupling

Loose coupling allows components to evolve independently without breaking the system. This principle reduces the blast radius of changes and failures.

Asynchronous communication, message queues, and well-defined APIs all support loose coupling. Tightly coupled systems may work initially, but struggle as they scale.

In interviews, loose coupling often appears as a distinguishing factor between junior and senior-level designs.

The Principle Of Data Locality

Data locality refers to keeping data close to where it is processed. This principle improves performance by reducing network hops and latency.

Sharding, caching, and regional replication all rely on data locality. However, optimizing for locality can complicate consistency and recovery.

Interviewers may test this principle by asking how global systems serve users across regions efficiently.

The Principle Of Graceful Degradation

Distributed systems should continue to provide partial functionality even when components fail. Graceful degradation prioritizes core functionality over completeness.

For example, a system might serve cached data when the primary database is unavailable or disable non-critical features during high load.

Candidates who design systems that fail gracefully demonstrate practical experience with real-world constraints.

How Interviewers Evaluate Your Understanding Of Principles

Interviewers rarely ask direct questions about distributed systems principles. Instead, they observe how naturally these principles appear in your reasoning.

Do you assume the network is reliable, or do you design around uncertainty? Do you acknowledge trade-offs, or do you search for perfect solutions? Do you think about failures before being prompted?

Strong candidates internalize these principles so deeply that they shape every design decision.

Common Mistakes Candidates Make

One common mistake is treating distributed systems as scaled-up monoliths. Another is over-indexing on tools instead of principles.

Candidates also frequently ignore operational concerns such as monitoring, recovery, and human error, which are central to real-world systems.

Conclusion

Distributed systems principles are the foundation of modern System Design. They explain why systems behave unpredictably, why trade-offs are unavoidable, and why engineering at scale is fundamentally different from local development.

In System Design interviews, your goal is not to recite definitions but to demonstrate principled thinking. When your designs reflect these principles naturally, interviewers see you as someone who can reason under uncertainty and build systems that survive real-world conditions.

Mastering distributed systems principles does not just improve interview performance; it shapes how you think as an engineer working on complex, scalable systems.