System Design Roadmap: A step-by-step guide for System Design interviews

System Design is often misunderstood as a collection of diagrams, patterns, or buzzwords. In reality, it is a way of thinking about software systems under real-world constraints. It asks how systems behave as they grow, how they fail, and how they evolve over time. This includes handling traffic spikes, partial outages, data growth, and changing business requirements without breaking user trust.

What makes System Design difficult is that there is rarely a single correct answer. Most design decisions involve trade-offs between performance, availability, consistency, cost, and complexity. Interviewers are not looking for perfection. They are looking for structured reasoning.

Why most people struggle without a roadmap

Many engineers approach System Design reactively. They jump straight into designing large systems like social networks or video platforms without mastering the fundamentals that make those systems possible. This leads to shallow answers, overuse of patterns, and confusion when interviewers push deeper.

A roadmap provides order. It ensures you learn concepts in the sequence your brain can actually internalize them. Instead of memorizing architectures, you build intuition step by step, which is what interviews are really testing.

What a good System Design roadmap gives you

A strong roadmap does three things. First, it helps you understand which concepts matter most at your level. Second, it prevents gaps that interviewers can easily expose. Third, it gives you confidence, because you know why you made a design decision rather than hoping it sounds correct.

System Design interviews reward clarity and structure. A roadmap is how you build both.

How System Design interviews are evaluated

System Design interviews are not judged on whether your design matches a reference architecture. They are evaluated on how you approach ambiguity, how you break down problems, and how you communicate trade-offs. Interviewers want to see that you can reason from first principles rather than recite patterns.

Your ability to ask clarifying questions is often evaluated before you even draw anything. Jumping into design too early is a common mistake and a negative signal.

Core evaluation dimensions

Across companies and levels, interviewers consistently assess four dimensions:

- Problem framing and requirement clarification

- Architectural clarity at a high level

- Depth in critical areas such as data, scaling, and failure handling

- Ability to explain trade-offs and justify decisions

Strong candidates make their thinking visible. Weak candidates focus on components without explaining why they exist.

How expectations change with seniority

The same System Design question is evaluated very differently depending on the level. Understanding this progression helps you tailor your preparation and avoid over- or under-designing.

| Level | What interviewers primarily evaluate |

| Junior | Clear explanation of basic components and request flow |

| Mid-level | Scalability, bottlenecks, and failure scenarios |

| Senior | Ambiguity handling, consistency guarantees, and real-world constraints |

This table explains why a roadmap matters. You are not just learning more topics. You are learning how to reason at a higher level of abstraction.

The System Design learning roadmap (high-level view)

System Design concepts build on each other. Trying to learn advanced distributed systems without understanding basic request flow or data modeling leads to fragile knowledge. A roadmap organizes learning into phases so each concept has context.

Early phases focus on understanding how systems work at a basic level. Later phases focus on how systems behave under stress, scale, and failure. Skipping phases almost always shows up in interviews.

The roadmap as a progression of thinking

The roadmap mirrors how interview difficulty increases. Early interviews test fundamentals. Later interviews test judgment, trade-offs, and experience-driven reasoning. Each phase prepares you for a different kind of question.

| Phase | Focus | What you gain |

| Phase 1 | Fundamentals | Clear mental models |

| Phase 2 | Data and APIs | Correct system boundaries |

| Phase 3 | Scalability | Growth-ready designs |

| Phase 4 | Distributed systems | Failure-aware thinking |

| Phase 5 | Advanced patterns | Real-world system fluency |

| Phase 6 | Interview practice | Confident execution |

This structure helps you see System Design as a journey rather than a checklist.

Iteration is part of the roadmap

The roadmap is not strictly linear. As you learn advanced topics, you will revisit fundamentals with a deeper understanding. This loop is intentional. Strong System Designers continuously refine their mental models rather than moving on permanently.

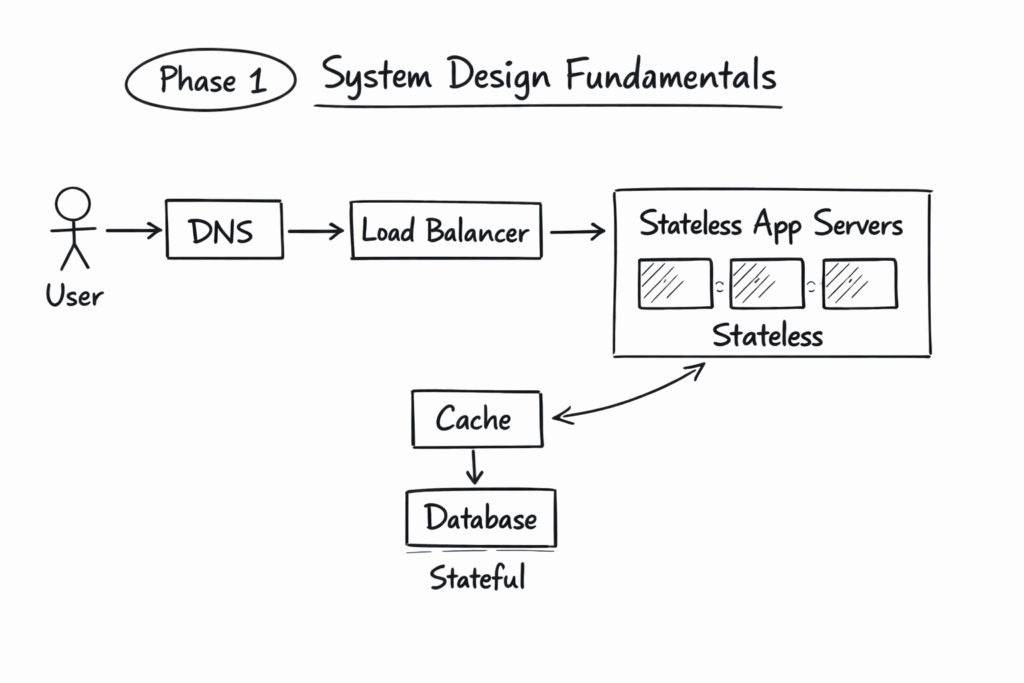

Phase 1: System Design fundamentals

Phase 1 is where most candidates underestimate the depth required. Fundamentals may look simple, but interviewers can quickly tell whether your understanding is shallow or internalized. Almost every System Design answer depends on these basics.

Without strong fundamentals, advanced concepts feel abstract, and interviews feel overwhelming.

Request lifecycle and system boundaries

You should be able to clearly explain what happens when a user makes a request. This includes how traffic flows through DNS, load balancers, application servers, and databases, and where latency and failures can occur. This mental model becomes the backbone of every design discussion.

Understanding boundaries is equally important. Knowing where responsibilities begin and end prevents over-coupled designs.

Stateless vs stateful services

One of the most important early concepts is the difference between stateless and stateful services. Stateless services scale more easily, recover faster, and simplify deployment. State introduces complexity around consistency, recovery, and coordination.

You should be comfortable explaining why state is often pushed to databases, caches, or external systems, and what trade-offs that introduces.

Core building blocks and performance intuition

Phase 1 also builds intuition around core components such as load balancers, caches, and databases. This includes understanding when caching helps, when it hurts, and how read-heavy and write-heavy workloads behave differently.

Equally important is basic performance intuition. You should be able to reason about latency, throughput, and bottlenecks without relying on precise numbers. Interviewers care more about your reasoning than exact calculations.

| Fundamental concept | Why interviewers care |

| Request flow | Shows system-level thinking |

| Stateless services | Enables scalability |

| Caching | Reveals performance intuition |

| Bottlenecks | Shows problem-solving depth |

Phase 1 is not about memorizing components. It is about building clarity. Once this clarity exists, everything else in the System Design roadmap becomes easier and more intuitive.

Phase 2: Data modeling and API design

In real systems, scalability and performance issues often trace back to poor data modeling rather than missing infrastructure. Interviewers know this, which is why they pay close attention to how candidates think about data early in a design.

Phase 2 is about learning to design systems from the data outward. Instead of asking “what services do I need,” you start asking “what data exists, how does it change, and who owns it.” This shift dramatically improves design quality.

Entity modeling and ownership boundaries

A strong System Design begins with identifying core entities and defining ownership clearly. Ownership determines which service is responsible for creating, updating, and validating data. Without clear ownership, systems become tightly coupled and fragile.

Interviewers look for candidates who can explain why data should not be shared or mutated freely across services. Clear ownership enables independent scaling and safer evolution.

Read vs write patterns and their impact

Not all data is used the same way. Some systems are read-heavy, others write-heavy, and many have asymmetric patterns. Understanding these patterns guides decisions around normalization, caching, and storage choice.

A key insight interviewers expect is that optimizing reads often increases write complexity, and vice versa. Recognizing this trade-off early leads to more realistic designs.

| Data pattern | Common design implication |

| Read-heavy | Denormalization, caching |

| Write-heavy | Normalization, batching |

| Mixed | CQRS-style separation |

API design as a system boundary

APIs define how systems interact. Good API design prevents cascading failures and preserves flexibility. In interviews, APIs are evaluated not on naming, but on semantics, consistency, and evolvability.

You should be comfortable explaining synchronous vs asynchronous APIs, pagination strategies, and idempotent writes. These choices directly affect scalability and failure handling.

Versioning, backward compatibility, and change safety

APIs are long-lived contracts. Breaking changes are expensive and risky. Interviewers expect candidates to understand why versioning and backward compatibility must be considered upfront rather than added later.

Phase 2 builds the habit of designing APIs that can evolve safely as requirements change.

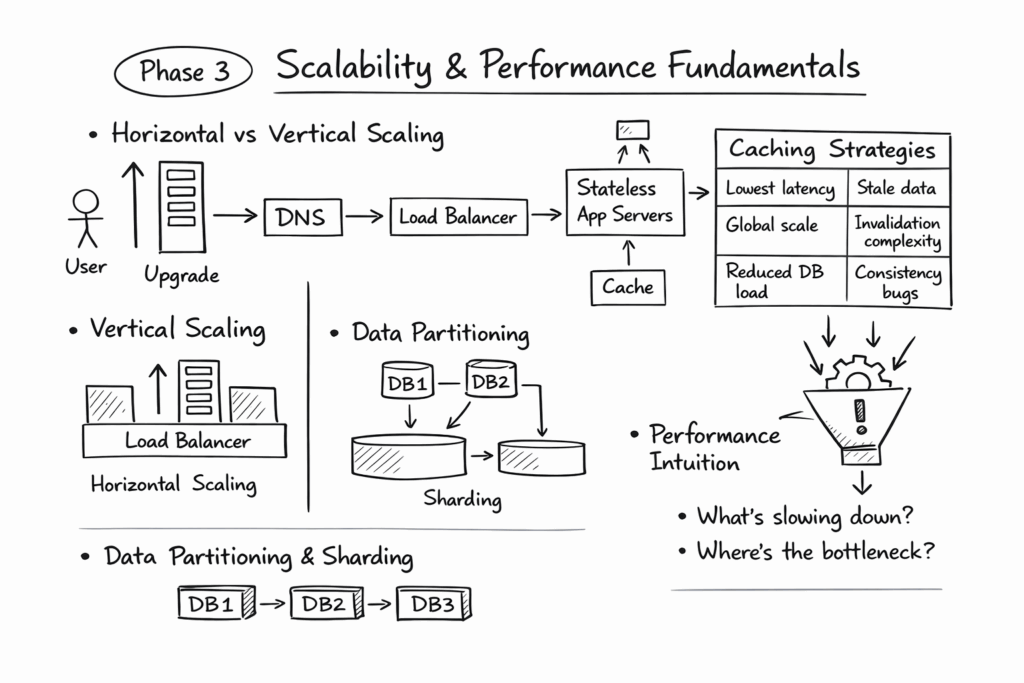

Phase 3: Scalability and performance fundamentals

Scalability is not just “handling more users.” It is about maintaining acceptable performance as load increases, without linear cost increases or operational instability. Interviewers want to see that you can identify bottlenecks before proposing solutions.

Phase 3 introduces the techniques that allow systems to grow predictably.

Horizontal vs vertical scaling

Vertical scaling is simple but limited. Horizontal scaling is more complex but provides long-term growth. Interviewers expect candidates to understand why most large systems favor horizontal scaling despite added complexity.

You should be able to explain what makes a service horizontally scalable and what prevents it from scaling easily.

Caching strategies and their trade-offs

Caching is one of the most powerful performance tools, but also one of the most dangerous when misused. Phase 3 focuses on understanding when caching helps, where it should be applied, and how it affects consistency.

Interviewers often probe cache invalidation, staleness tolerance, and cache failure scenarios because they reveal depth of understanding.

| Cache layer | Typical benefit | Typical risk |

| Client | Lowest latency | Stale data |

| CDN | Global scale | Invalidation complexity |

| Server | Reduced DB load | Consistency bugs |

Data partitioning and sharding

As datasets grow, single-node databases become bottlenecks. Partitioning distributes load but introduces complexity around routing, rebalancing, and cross-partition queries.

Strong candidates explain not just how to shard, but how sharding changes failure modes and operational complexity.

Performance intuition over exact numbers

Interviewers rarely expect precise calculations. They care about intuition. Can you explain why a system slows down? Can you identify the likely bottleneck? Phase 3 builds this intuition so your answers sound grounded rather than theoretical.

Phase 4: Distributed systems and failure handling

The defining characteristic of distributed systems is that failure is inevitable. Networks fail, machines crash, and dependencies become slow. Phase 4 teaches you to treat failure as the default case rather than an exception.

Interviewers use this phase to separate candidates who design for the happy path from those who design for reality.

Consistency, availability, and trade-offs

You should be able to explain why systems cannot have perfect consistency and availability at the same time under network partitions. More importantly, you should be able to explain which trade-off you choose and why.

Interviewers are less interested in hearing “CAP theorem” and more interested in how you apply it to real systems.

Timeouts, retries, and idempotency

Retries without timeouts can make failures worse. Timeouts without retries reduce availability. Idempotency allows safe retries. Phase 4 builds understanding of how these mechanisms work together.

Strong candidates explain failure-handling mechanisms as a coordinated system rather than isolated techniques.

Eventual consistency and user experience

Many distributed systems rely on eventual consistency. Phase 4 teaches how to design systems that are eventually consistent without confusing users or breaking correctness.

Interviewers look for candidates who can explain what users see during inconsistency windows and how the system recovers.

| Failure scenario | Typical design response |

| Service crash | Replication, restart |

| Network delay | Timeouts, retries |

| Partial outage | Graceful degradation |

Phase 5: Advanced System Design patterns

Advanced patterns make sense only when you understand the problems they solve. Introducing patterns too early leads to cargo-cult designs. Phase 5 comes after fundamentals, scalability, and distributed systems for a reason.

Interviewers expect you to apply patterns selectively, not by default.

Event-driven and asynchronous architectures

Pub-sub systems, event streams, and message queues enable decoupling and scalability. Phase 5 teaches when event-driven designs are appropriate and when they introduce unnecessary complexity.

Strong candidates explain both the benefits and the operational costs of asynchronous systems.

Coordination, rate limiting, and control planes

Advanced systems often need coordination mechanisms such as rate limiters, distributed locks, or leader election. These tools solve specific problems but can become bottlenecks if misused.

Interviewers value candidates who explain why coordination should be minimized rather than assumed.

Composing patterns into real systems

The most important skill in Phase 5 is composition. Real systems combine caching, queues, replication, and APIs in deliberate ways. Interviewers want to see that you can assemble these pieces coherently rather than listing them independently.

| Pattern | Problem it solves |

| Pub sub | Event fan-out |

| Rate limiter | Abuse protection |

| Saga | Long-running workflows |

| CQRS | Read/write separation |

Phase 5 is where System Design stops being theoretical and starts resembling real production systems.

Phase 6: Practicing real System Design interview questions

Many candidates understand System Design concepts but struggle to apply them under interview conditions. This phase exists to bridge that gap. System Design interviews are time-bound, interactive, and ambiguous. Practicing the process is just as important as knowing the material.

Interviewers are evaluating how you think in real time. Practicing full questions trains you to structure answers, manage time, and adapt to feedback.

A repeatable interview structure

Strong candidates follow a predictable structure that keeps the discussion focused and calm. You should practice this flow until it becomes automatic.

| Interview step | What interviewers want to see |

| Clarify requirements | Comfort with ambiguity |

| Define scope | Good judgment |

| High-level design | Clear mental model |

| Deep dives | Technical depth |

| Trade-offs | Engineering maturity |

Practicing this structure prevents you from getting lost in details too early or running out of time before addressing failures.

Choosing the right questions to practice

Not all System Design questions are equally valuable. Start with foundational systems such as URL shorteners, rate limiters, or file storage systems before moving to complex platforms like social networks or payment systems.

The goal is not variety, but repetition with reflection. Revisit the same question multiple times and improve your answer each time.

Practicing with feedback

Practicing alone helps, but feedback accelerates growth. Mock interviews, peer reviews, or even self-review using recordings can expose weaknesses in clarity, structure, or depth.

Interviewers reward candidates who improve during the interview itself. Practice trains that adaptability.

Common mistakes in learning System Design (and how to avoid them)

Memorizing architectures instead of reasoning

One of the most common mistakes is memorizing “standard” architectures and reproducing them regardless of context. Interviewers can detect this immediately.

Strong candidates explain why a component exists. Weak candidates explain what the component is.

Ignoring failure scenarios

Another frequent mistake is designing only for the happy path. Many candidates mention replication or retries, but cannot explain what actually happens during failure.

Interviewers expect you to proactively discuss failures rather than wait to be asked.

Over-designing too early

Candidates often jump into microservices, sharding, or event-driven systems before establishing basic requirements. This creates unnecessary complexity and signals a lack of judgment.

Good System Design is incremental. You earn complexity by justifying it.

| Weak approach | Strong approach |

| Jump to microservices | Start simple, evolve |

| Tool-first thinking | Problem-first reasoning |

| Perfect diagrams | Clear explanations |

Using buzzwords without clarity

Mentioning CAP theorem, eventual consistency, or CQRS without tying them to concrete decisions is a negative signal. Interviewers care about application, not vocabulary.

How long it takes to follow the System Design roadmap

System Design learning time depends heavily on background. Someone with backend experience will move faster than someone new to distributed systems. The roadmap is designed to be flexible, not rigid.

Consistency matters more than speed. Short, regular sessions outperform long, irregular study blocks.

Realistic preparation timelines

| Background | Typical preparation time |

| New to System Design | 3–4 months |

| Backend engineer | 6–8 weeks |

| Senior engineer refreshing | 3–4 weeks |

These timelines assume focused study and active practice, not passive reading.

Signs you are progressing correctly

Progress is not measured by how many topics you’ve covered. It is measured by how confidently you can reason about trade-offs and failures.

If your answers are becoming simpler, clearer, and more structured, you are on the right path.

Final checklist: are you System Design interview ready?

Before scheduling interviews, you should be able to answer “yes” to most of the following without hesitation. This checklist helps prevent premature interviewing, which can hurt confidence.

| Skill area | Ready |

| Explain the request lifecycle clearly | ☐ |

| Justify architectural choices | ☐ |

| Reason about scalability | ☐ |

| Handle failures confidently | ☐ |

| Discuss trade-offs explicitly | ☐ |

| Communicate clearly under pressure | ☐ |

Unchecked boxes highlight where to focus next, not reasons to panic.

What interview readiness actually feels like

Being ready does not mean knowing everything. It means being comfortable saying “it depends,” asking clarifying questions, and reasoning through uncertainty without freezing.

Interviewers are far more forgiving of missing details than of unclear thinking.

Use structured prep resources effectively

Use Grokking the System Design Interview on Educative to learn curated patterns and practice full System Design problems step by step. It’s one of the most effective resources for building repeatable System Design intuition.

You can also choose the best System Design study material based on your experience:

Final thoughts

System Design is not mastered through shortcuts or memorization. It is built through structured learning, repeated practice, and reflection. A roadmap exists to protect you from randomness and overwhelm, not to rush you toward advanced topics.

Treat this roadmap as iterative. Revisit earlier phases as your understanding deepens. The strongest System Designers are not those who know the most patterns, but those who can reason calmly and clearly when systems become complex.

If you follow this roadmap with intent and consistency, System Design interviews stop feeling like guesswork and start feeling like conversations you are prepared to lead.