System Design Problems: How to Approach and Solve Interview Questions Effectively

System Design problems are not meant to test whether you can design a perfect system. They exist to evaluate how you think through ambiguity, structure complex ideas, and communicate trade-offs under pressure. Interviewers intentionally choose problems that do not have a single correct answer because real-world systems rarely do.

A candidate who proposes a reasonable design and explains it clearly often performs better than one who proposes an ambitious design without justification. The problem itself is simply a vehicle for observing reasoning.

Why open-ended problems are so effective

Unlike coding problems, system design interview questions do not constrain you to a fixed input or output. This allows interviewers to explore how you prioritize, what assumptions you make, and how you respond when those assumptions are challenged.

These problems reveal whether you can operate without a detailed specification, which is a critical skill for senior engineers. Interviewers are less interested in whether your design is complete and more interested in whether it is coherent and defensible.

What System Design problems reveal about seniority

As roles become more senior, System Design problems carry more weight. Interviewers use them to assess judgment, restraint, and experience. Candidates who jump into complexity too quickly or treat the problem like a puzzle often struggle at higher levels.

Strong candidates use System Design problems to demonstrate clarity, composure, and intentional decision-making. These qualities matter more than technical breadth.

How interviewers evaluate answers to System Design problems

Interviewers evaluate System Design problems by observing how candidates move through the discussion. They pay attention to the order in which ideas are introduced, how decisions are justified, and how well the candidate maintains a coherent narrative.

A design that evolves logically during the conversation is usually rated higher than a static design presented all at once. Interviewers want to see thinking happen in real time.

Signals interviewers actively listen for

Interviewers listen for signs of structured reasoning and practical judgment. They notice whether candidates clarify requirements before designing, whether they explain trade-offs instead of asserting choices, and whether they acknowledge uncertainty where appropriate.

Communication style also plays a major role. Clear explanations using simple language signal deep understanding, while dense terminology without explanation often signals shallow familiarity.

| Interview signal | What it indicates |

| Clear structure | Organized thinking |

| Trade-off discussion | Engineering judgment |

| Failure awareness | Real-world experience |

| Calm adaptation | Senior-level maturity |

These signals often outweigh the specific technologies or architectures mentioned.

Why follow-up questions matter more than the initial design

The initial design is rarely the most important part of the interview. Follow-up questions are where interviewers probe in depth. They may introduce new constraints, change scale assumptions, or ask about failure scenarios.

Strong candidates treat these follow-ups as natural extensions of the same problem. They adjust their design incrementally and explain the impact of changes clearly. This adaptability is one of the strongest positive signals in System Design interviews.

A repeatable framework for approaching System Design problems

System Design problems vary widely in domain, but the approach should remain consistent. A repeatable framework reduces cognitive load and prevents panic when the problem feels unfamiliar. Interviewers expect experienced candidates to follow a recognizable flow, even if they never explicitly label it.

Candidates who approach every problem differently often appear scattered or reactive. Candidates who use a consistent structure appear calm and deliberate, even when solving a new problem.

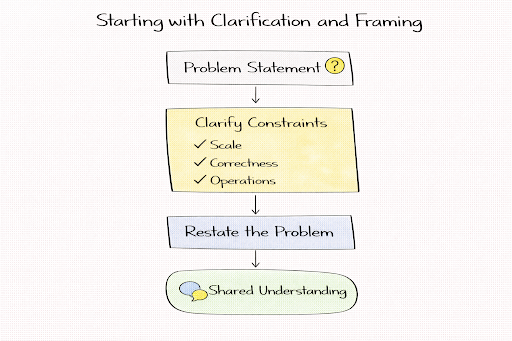

Starting with clarification and framing

Every System Design problem begins with understanding what is being asked. Before proposing any architecture, strong candidates clarify what the system must do and what constraints matter most. This includes scale expectations, correctness requirements, and operational assumptions.

Framing the problem in your own words helps ensure alignment with the interviewer and demonstrates deliberate thinking. It also gives you a stable reference point as the discussion becomes more complex.

Progressing from high-level design to depth

After clarification, strong candidates establish a high-level design that outlines major components and request flow. This creates a shared mental model before diving into details. From there, depth is added selectively in areas that matter most for the problem.

This progression mirrors how real systems are designed and how interviewers expect candidates to reason. Jumping into details too early often leads to confusion and over-design.

Treating the problem as a collaborative discussion

System Design problems are conversations, not monologues. Interviewers guide depth through questions and constraint changes. A structured approach allows candidates to adapt without losing coherence.

Strong candidates anchor follow-up discussions to earlier decisions and explain how changes propagate through the design rather than starting over. This incremental reasoning is a key interview signal.

Beginner System Design problems and foundational thinking

Beginner System Design problems are often used as early filters. These problems test foundational thinking rather than scale or distributed complexity. Interviewers want to see whether candidates can explain request flow, define boundaries, and model simple data correctly.

Candidates who struggle with beginner problems usually struggle later, regardless of how advanced their knowledge appears. This makes these problems disproportionately important.

What interviewers expect at the beginner level

At this stage, interviewers primarily evaluate structure and communication. They expect candidates to describe how a request moves through the system, identify core components, and explain why those components exist.

Optimization is not the goal. Over-designing a beginner problem often signals weak judgment rather than ambition.

| Focus area | What interviewers evaluate |

| Request flow | End-to-end clarity |

| Boundaries | Separation of concerns |

| Data modeling | Simplicity and correctness |

| Trade-off awareness | Conceptual understanding |

Typical characteristics of beginner System Design problems

Beginner problems usually involve a small number of operations and modest scale assumptions. Examples include URL shorteners, basic file storage systems, or simple rate limiters. While the domain may vary, the expected reasoning remains consistent.

Interviewers are not testing creativity at this stage. They are testing whether candidates can explain fundamentals clearly and confidently.

Why beginner problems set the tone for the interview

The way a candidate handles a beginner problem often shapes the rest of the interview. Clear structure, calm explanation, and reasonable assumptions build the interviewer’s confidence early. That confidence often leads to more collaborative and exploratory follow-up questions later.

Strong candidates treat beginner problems as opportunities to demonstrate clarity rather than rushing toward complexity.

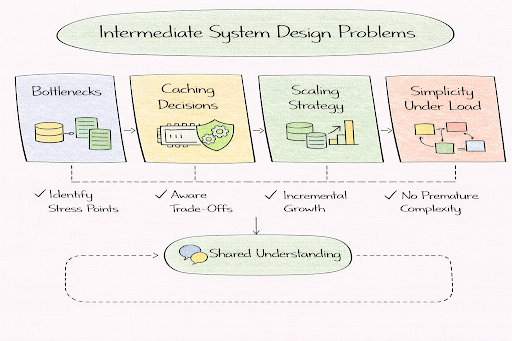

Intermediate System Design problems and scalability intuition

Intermediate System Design problems introduce scale as a first-class concern. At this stage, the system must continue to perform acceptably as traffic grows, which forces candidates to think beyond basic correctness. Interviewers use these problems to evaluate whether candidates can reason about growth, bottlenecks, and gradual evolution.

The key transition here is moving from “how does this work?” to “how does this behave as load increases?”

What interviewers expect in intermediate problems

Interviewers expect candidates to identify pressure points before proposing solutions. Rather than immediately adding caches or queues, strong candidates explain which component becomes the bottleneck and why. This shows performance intuition rather than pattern memorization.

Candidates are also expected to explain how the system would evolve over time. Interviewers prefer designs that start simple and gain complexity only when justified by traffic or usage patterns.

| Design dimension | What interviewers evaluate |

| Bottleneck identification | Performance intuition |

| Scaling approach | Long-term thinking |

| Caching decisions | Trade-off awareness |

| System evolution | Engineering judgment |

Typical intermediate System Design problems

Problems such as news feeds, notification systems, search autocomplete, or media hosting platforms often fall into this category. These systems expose candidates to read-heavy or write-heavy workloads and introduce realistic performance constraints without deep distributed coordination.

Interviewers care less about the specific technologies mentioned and more about whether the reasoning behind each decision is sound.

Common pitfalls at the intermediate level

A frequent mistake is assuming massive scale without justification. Candidates sometimes design for billions of users when the problem does not require it, leading to unnecessary complexity. Interviewers interpret this as weak judgment rather than ambition.

Strong candidates show restraint and clearly explain when additional complexity becomes necessary.

Advanced System Design problems and distributed systems depth

Advanced System Design problems involve distributed systems behavior that cannot be ignored. These problems introduce multiple services, coordination challenges, consistency trade-offs, and failure scenarios that fundamentally shape the architecture.

Interviewers use these problems to differentiate strong mid-level candidates from senior engineers.

What interviewers probe in advanced problems

Interviewers expect candidates to reason about partial failures, network delays, and coordination costs. They listen for whether candidates design systems that degrade gracefully rather than collapse under stress.

Answers that assume reliable networks or perfect synchronization are quickly challenged. Strong candidates acknowledge uncertainty and explain how the system behaves when assumptions fail.

| Distributed concern | What it reveals |

| Consistency choice | User-impact reasoning |

| Coordination awareness | Scalability maturity |

| Failure handling | Resilience thinking |

| Recovery behavior | Operational experience |

Typical advanced System Design problems

Examples include messaging systems, distributed schedulers, coordination services, or globally replicated data stores. These systems force candidates to balance availability, consistency, and performance under uncertainty.

Interviewers do not expect protocol-level precision. They expect clear explanations of trade-offs and consequences.

How strong candidates approach advanced problems

Strong candidates move slowly and explain their reasoning step by step. They make assumptions explicit and adjust them when challenged. Interviewers value this calm, methodical approach far more than complex architectures.

Advanced problems reward clarity and composure over cleverness.

Data-heavy System Design problems

In data-heavy System Design problems, data modeling decisions dominate the architecture. These problems test whether candidates understand how data shapes scalability, consistency, and coupling. Interviewers often use these problems to probe depth early.

The hardest part is not infrastructure. It is deciding how data should be structured, owned, and evolved.

What interviewers focus on in data-heavy problems

Interviewers pay close attention to how candidates identify core entities and relationships. They listen for clarity around ownership boundaries and update paths. Systems that allow multiple services to modify the same data directly are viewed as fragile.

Candidates are also expected to reason from access patterns. Whether data is read frequently, written frequently, or both influences nearly every design decision.

| Data concern | Interview focus |

| Entity modeling | Structural clarity |

| Ownership | Coupling control |

| Consistency needs | Correctness judgment |

| Access patterns | Performance intuition |

Typical data-heavy System Design problems

E-commerce platforms, booking systems, financial ledgers, and analytics pipelines are common examples. These systems often require strong correctness guarantees and careful handling of concurrency.

Interviewers expect candidates to explain why data is modeled a certain way and how that model supports the system’s behavior over time.

Why data-heavy problems expose weak fundamentals

Candidates with shaky fundamentals often struggle here because data decisions force precise thinking. There is little room for vague explanations. Strong candidates rely on principles such as single ownership and clear boundaries to guide their designs.

Real-time and low-latency System Design problems

Real-time System Design problems introduce strict latency requirements. Systems such as chat applications, live collaboration tools, or streaming platforms must respond quickly and predictably to user actions.

Interviewers use these problems to test whether candidates understand latency as a first-class constraint rather than an afterthought.

What interviewers expect in low-latency designs

Interviewers expect candidates to explain where latency comes from and how it accumulates across the request path. They listen for reasoning about critical paths, concurrency, and trade-offs between responsiveness and consistency.

Strong candidates explain how relaxing certain guarantees improves user experience and what the user sees during transient inconsistencies.

| Latency concern | What it reveals |

| Critical path reasoning | Performance intuition |

| Trade-off clarity | Practical judgment |

| Backpressure handling | System stability awareness |

Typical real-time System Design problems

Examples include chat systems, collaborative editors, live feeds, and streaming services. These systems often involve ordering, delivery guarantees, and concurrency challenges.

Interviewers do not expect perfect solutions. They expect thoughtful reasoning grounded in user experience and system behavior.

Common mistakes in real-time problems

A common mistake is treating real-time systems like batch systems. Candidates may over-prioritize durability or strict consistency at the expense of responsiveness. Interviewers prefer candidates who recognize that real-time systems require different trade-offs.

Platform and infrastructure System Design problems

Platform and infrastructure System Design problems shift the focus away from user-facing features and toward system enablement. In these problems, the system exists to support other systems rather than end users directly. Interviewers use them to assess architectural maturity and operational awareness.

Candidates who perform well here demonstrate an understanding that reliability, isolation, and safe evolution often matter more than feature richness.

What interviewers look for in platform problems

Interviewers expect candidates to reason about the separation of concerns. Concepts such as control plane versus data plane, configuration safety, and blast radius containment become central. Candidates who mix responsibilities or treat configuration as an afterthought often produce brittle designs.

Interviewers also listen to how candidates think about change. Platform systems must evolve without breaking dependent services, which requires careful rollout and isolation strategies.

| Platform concern | What interviewers evaluate |

| Control and data plane separation | Operational maturity |

| Isolation boundaries | Risk containment |

| Configuration handling | Change safety |

| Dependency management | Reliability thinking |

Typical platform System Design problems

Problems such as content delivery networks, deployment systems, API gateways, coordination services, and observability platforms commonly appear in this category. These systems emphasize predictability, stability, and safe failure over raw performance.

Interviewers expect candidates to explain how these platforms protect downstream systems rather than amplify failures.

Why platform problems differentiate senior candidates

Candidates who succeed in platform-focused problems show that they think beyond individual services. They understand how systems interact at scale and how architectural decisions affect many teams over time. This perspective strongly differentiates senior engineers from mid-level ones.

How to adapt System Design problems when constraints change

Interviewers often modify requirements mid-discussion to test adaptability. This reflects real-world engineering, where constraints shift due to business needs, technical discoveries, or operational realities.

Candidates who treat constraint changes as disruptions often struggle. Candidates who treat them as natural inputs perform better.

Anchoring adaptations to earlier decisions

Strong candidates do not restart their design when constraints change. Instead, they reference earlier assumptions and explain how the new constraint affects specific components or trade-offs.

This approach preserves coherence and shows that the original structure was thoughtfully chosen rather than accidental.

Explaining trade-offs during adaptation

Adapting a design requires acknowledging consequences. Candidates should explain what improves and what degrades as a result of the change. Interviewers value candidates who communicate these trade-offs clearly and calmly.

Defensiveness or rigidity during this phase is a negative signal.

Why adaptability often outweighs initial design quality

Interviewers frequently rate candidates higher for graceful adaptation than for a strong initial design. The ability to adjust under pressure reflects real engineering behavior more accurately than producing an idealized architecture.

Candidates who adapt well signal maturity and collaboration skills.

Common mistakes candidates make with System Design problems

Jumping into architecture too early

One of the most frequent mistakes is starting with components before clarifying requirements. This often leads to misaligned designs and wasted effort. Interviewers interpret this as poor problem framing rather than enthusiasm.

Strong candidates slow down early to ensure alignment.

Over-designing without justification

Many candidates assume massive scale or advanced requirements without being prompted. This leads to unnecessary complexity and signals weak judgment. Interviewers prefer designs that grow logically from stated constraints.

Simplicity early is a positive signal.

Ignoring failure scenarios

Candidates sometimes design systems that work only in ideal conditions. Interviewers quickly expose this weakness by asking about failures. Designs that collapse under failure lose credibility.

Strong candidates proactively discuss failure behavior and recovery.

| Common mistake | Interview interpretation |

| Skipping clarification | Disorganized thinking |

| Over-engineering | Poor judgment |

| Ignoring failures | Lack of experience |

| Listing components | Shallow understanding |

Treating System Design problems like exams

Candidates who treat System Design problems as tests often sound rigid and defensive. Interviewers prefer candidates who think aloud, explore alternatives, and adjust collaboratively.

System Design interviews reward reasoning, not memorization.

How to practice System Design problems effectively

System Design practice is not about speed or correctness. It is about clarity, structure, and communication. Practicing silently or focusing only on diagrams is insufficient.

Candidates must practice explaining their thinking out loud.

Repetition and refinement over novelty

Solving many different problems once is less effective than solving a shorter set multiple times. Each iteration should improve clarity, pacing, and trade-off explanation.

Interviewers notice this refinement immediately.

Practicing under realistic interview conditions

Effective practice includes time limits, interruptions, and changing constraints. This builds composure and prepares candidates for real interview dynamics.

Mock interviews and peer feedback accelerate improvement by revealing blind spots.

Using problems as thinking tools

The goal of practice is not to memorize solutions. It is to internalize patterns and reasoning strategies. Strong candidates use System Design problems to build intuition rather than collect architectures.

Using structured prep resources effectively

Use Grokking the System Design Interview on Educative to learn curated patterns and practice full System Design problems step by step. It’s one of the most effective resources for building repeatable System Design intuition.

You can also choose the best System Design study material based on your experience:

Final thoughts

System Design problems are not puzzles to solve or templates to memorize. They are tools for evaluating how candidates think under uncertainty. Interviewers care about clarity, judgment, and adaptability far more than technical completeness.

Candidates who develop a repeatable approach, explain trade-offs calmly, and adapt gracefully consistently perform well. Once this mindset is in place, unfamiliar problems feel manageable, and interviews become collaborative discussions rather than stressful exams.

Mastering System Design problems ultimately means mastering a way of thinking. That skill extends beyond interviews and into real-world engineering, where ambiguity, trade-offs, and evolving constraints are the norm.