ZooKeeper System Design: a complete System Design interview guide

When an interviewer asks you to explain or design ZooKeeper, they are not asking you to build a CRUD service or a coordination wrapper around a database. They are testing whether you understand distributed coordination as a first-class systems problem. ZooKeeper represents a category of systems whose primary responsibility is not storing business data, but enforcing correctness, ordering, and agreement across unreliable machines.

In a System Design interview, ZooKeeper is used as a proxy to evaluate your grasp of core distributed systems concepts. These include consistency models, leader-based replication, quorum systems, failure detection, and recovery under partial failures. Interviewers want to see whether you can reason about correctness before performance, and whether you understand why coordination problems are fundamentally harder than data storage problems.

Designing ZooKeeper means designing a coordination service that many other distributed systems depend on for correctness. Any mistake in its guarantees can cascade into system-wide failures. That is why interviews emphasize clarity of guarantees, failure behavior, and trade-offs rather than feature richness or throughput.

Why systems like ZooKeeper exist

As distributed systems grow, individual services must coordinate with one another. They need to agree on leaders, manage configuration consistently, detect failures, and ensure that only one node performs certain critical tasks at a time. Without a coordination mechanism, each system ends up re-implementing its own version of leader election, locking, and membership tracking, often incorrectly.

The core problem is that distributed systems operate in environments where messages can be delayed, reordered, or lost, and where nodes can fail independently. In such environments, coordination is not just about communication; it is about agreement under uncertainty.

Why ad hoc coordination fails at scale

Early distributed systems often relied on shared databases or best-effort heartbeats for coordination. These approaches break down as systems scale. Databases are not designed to provide the ordering and session semantics required for coordination, and ad hoc heartbeat systems struggle with false positives, split-brain scenarios, and race conditions.

As systems become more complex, coordination logic spreads across services, making it difficult to reason about correctness. Debugging failures becomes extremely difficult because there is no single source of truth for the system state.

ZooKeeper exists to centralize and standardize coordination logic so that application developers do not need to solve these problems repeatedly.

ZooKeeper as a coordination primitive

ZooKeeper is designed to be a shared coordination service that multiple distributed systems can rely on. Instead of embedding coordination logic inside each application, ZooKeeper provides a small, well-defined set of primitives that can be composed to solve common coordination problems.

Importantly, ZooKeeper is not designed to be a general database or message queue. Its value lies in its strong guarantees around ordering, consistency, and failure handling. These guarantees allow other systems to be simpler, because they can delegate coordination concerns to ZooKeeper with confidence.

In interviews, it is important to articulate that ZooKeeper exists to simplify distributed System Design by providing correctness guarantees that are otherwise difficult to implement correctly.

Clarifying requirements and guarantees upfront

ZooKeeper’s design is driven almost entirely by its guarantees. Unlike application systems, where features can be added incrementally, coordination systems must define their guarantees upfront. Every architectural decision flows from these guarantees.

In interviews, failing to clearly state ZooKeeper’s guarantees often leads to confusion later when discussing architecture, consensus, or failure handling. Strong candidates explicitly anchor their explanation around what ZooKeeper promises and what it does not.

Consistency guarantees that ZooKeeper provides

ZooKeeper provides strong consistency for writes. All write operations are linearizable, meaning they appear to occur in a single global order that is consistent across the cluster. This property is critical for coordination because it ensures that all clients observe state changes in the same order.

ZooKeeper also provides FIFO ordering per client session. Requests from a single client are processed in the order they are sent, which simplifies reasoning about application behavior. This session ordering guarantee allows developers to build higher-level coordination patterns without complex synchronization logic.

However, ZooKeeper does not guarantee that all reads see the latest write unless explicitly synchronized. Understanding and explaining this nuance demonstrates depth of knowledge in interviews.

Availability and fault tolerance assumptions

ZooKeeper is designed to tolerate failures, but it prioritizes correctness over availability. It requires a quorum of nodes to be operational in order to process writes. If a quorum is not available, ZooKeeper becomes unavailable for writes rather than risking inconsistency.

This design choice aligns with the CAP theorem trade-off ZooKeeper makes. It chooses consistency and partition tolerance over availability. In interviews, explicitly stating this trade-off signals a strong understanding of distributed systems.

ZooKeeper assumes a crash-stop failure model rather than Byzantine failures. Nodes may fail or restart, but they do not act maliciously. This assumption simplifies the design and is standard for many coordination systems.

What ZooKeeper explicitly does not guarantee

ZooKeeper does not aim to provide high write throughput. Writes are intentionally serialized through a leader to preserve ordering and consistency. It also does not provide complex query capabilities or large data storage.

Clarifying what ZooKeeper does not do is just as important as explaining what it does. Interviewers often test whether candidates mistakenly treat ZooKeeper as a general database or misuse it for high-volume workloads.

Setting the stage for the rest of the design

Once guarantees are clear, the rest of ZooKeeper’s design becomes easier to explain. Leader election, consensus protocols, read and write paths, and failure handling all exist to uphold these guarantees.

In interviews, clearly framing requirements and guarantees upfront creates a strong narrative. It shows that your design choices are intentional and rooted in correctness rather than convenience.

Core abstractions and data model

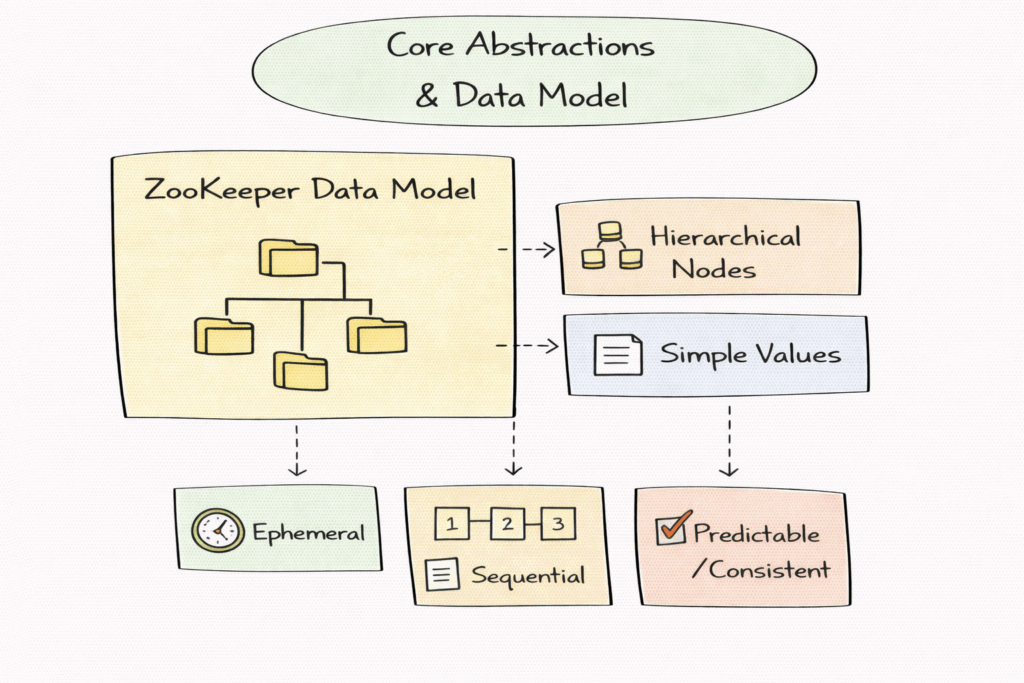

ZooKeeper’s data model is deliberately minimal because its primary role is coordination, not data storage. A simpler model reduces ambiguity and makes correctness easier to reason about under failures. In interviews, it is important to emphasize that ZooKeeper optimizes for predictability and consistency rather than expressiveness.

The data model supports just enough structure to enable common coordination patterns while avoiding features that could compromise ordering guarantees or performance predictability.

Hierarchical namespace and znodes

ZooKeeper exposes a hierarchical namespace that resembles a filesystem. Each node in this hierarchy is called a znode. This structure allows applications to organize coordination state logically and discover related information through parent–child relationships.

Unlike filesystem files, znodes are not designed to store large amounts of data. They typically contain small metadata or configuration values. In interviews, explicitly stating that znodes are meant for metadata rather than bulk data helps avoid a common misunderstanding.

Persistent, ephemeral, and sequential znodes

Persistent znodes remain in the system until explicitly deleted. They are often used to store configuration or long-lived coordination state. Ephemeral znodes are tied to a client session and are automatically removed when the session ends. This property is fundamental to failure detection and membership tracking.

Sequential znodes include a monotonically increasing sequence number in their name. They are crucial for implementing ordering-based coordination patterns such as leader election and distributed queues. Interviewers often expect candidates to explain why sequence numbers are generated by ZooKeeper rather than clients.

Watches as a coordination mechanism

ZooKeeper allows clients to set watches on znodes. Watches notify clients when data or children change. They are one-time triggers rather than persistent subscriptions. This design choice avoids an unbounded notification state and keeps the system scalable.

In interviews, it is important to highlight that watches are a hint mechanism rather than a reliable event stream. Clients must always re-read the state after receiving a notification.

High-level architecture overview

ZooKeeper is implemented as a replicated state machine. All servers maintain the same in-memory state, and state transitions occur through an ordered sequence of transactions. This model ensures strong consistency as long as all servers apply transactions in the same order.

In interviews, describing ZooKeeper in terms of a replicated state machine immediately signals a strong distributed systems understanding.

Cluster roles and server types

A ZooKeeper cluster consists of multiple servers, typically an odd number to support quorum-based decisions. At any time, one server acts as the leader while the others act as followers. Some deployments also include observers, who receive state updates but do not participate in quorum decisions.

The leader is responsible for ordering all write requests. Followers process read requests and participate in consensus for writes. Observers improve read scalability without affecting write quorum size.

Client interaction with the cluster

Clients connect to a ZooKeeper ensemble rather than a specific server. They can send read requests to any server, but write requests are always forwarded to the leader. This design allows reads to scale horizontally while preserving a single global write order.

Interviewers often probe whether candidates understand why allowing writes on followers would break ZooKeeper’s guarantees.

Request flow at a high level

When a write request arrives, it is forwarded to the leader, proposed to followers, and committed once a quorum acknowledges it. Reads can be served locally, but may not always reflect the most recent committed write unless additional synchronization is performed.

This asymmetry between reads and writes is a defining architectural characteristic of ZooKeeper.

Leader election and cluster membership

ZooKeeper relies on a single leader to serialize write operations. This avoids the complexity of multi-leader consensus and simplifies ordering guarantees. The leader acts as the source of truth for the transaction order.

In interviews, it is important to explain that the leader is not a performance optimization but a correctness requirement.

Leader election process

When a ZooKeeper cluster starts or loses its leader, it enters a leader election phase. Each server proposes itself using a unique identifier and its latest transaction history. The server with the most up-to-date state and the highest priority is elected leader.

This ensures that the new leader has all committed transactions before accepting new writes. Interviewers often care more about this property than the exact election algorithm.

Handling membership changes

ZooKeeper supports dynamic cluster membership changes, but these operations are rare and carefully controlled. Adding or removing servers requires coordination to avoid inconsistent views of quorum membership.

Explaining that membership changes are intentionally conservative shows awareness of the risks involved in reconfiguration.

Leader responsibilities during normal operation

Once elected, the leader assigns transaction identifiers, broadcasts proposals, and commits transactions. It also maintains heartbeat communication with followers to detect failures.

In interviews, emphasizing the leader’s role in maintaining global order reinforces understanding of ZooKeeper’s consistency model.

Consensus and the ZooKeeper Atomic Broadcast (ZAB) protocol

ZooKeeper uses the ZooKeeper Atomic Broadcast protocol rather than a generic Paxos implementation. ZAB is tailored specifically for leader-based systems with a single active leader at a time.

In interviews, it is sufficient to explain that ZAB ensures all servers agree on the same sequence of state transitions.

Proposal, acknowledgment, and commit phases

When the leader receives a write request, it assigns a transaction ID and broadcasts a proposal to followers. Followers acknowledge the proposal after persisting with it. Once the leader receives acknowledgments from a quorum, the transaction is committed.

This two-phase process ensures durability and ordering even if failures occur during execution.

Recovery and synchronization phases

ZAB includes a recovery mode that runs during leader election. In this mode, the new leader synchronizes the state with followers to ensure no committed transactions are lost.

Interviewers often test whether candidates understand that ZooKeeper must not accept new writes until synchronization completes.

Guarantees provided by ZAB

ZAB guarantees that all committed transactions are delivered in the same order to all servers. It also guarantees that once a transaction is committed, it will not be rolled back.

These guarantees form the backbone of ZooKeeper’s consistency model.

Read and write request handling

All write requests are funneled through the leader. This includes creating znodes, updating data, and deleting nodes. Serializing writes ensures a single global order and prevents conflicting updates.

In interviews, explaining why this limits write throughput but simplifies correctness is critical.

Read request handling

Read requests can be served by any server. This allows ZooKeeper to scale reads efficiently. However, because reads may be served from a follower, they may not reflect the most recent write.

ZooKeeper provides synchronization mechanisms to allow clients to ensure they see the up-to-date state when required.

Consistency trade-offs for reads

ZooKeeper’s read model is a deliberate trade-off. Allowing local reads improves performance and scalability, but clients must explicitly request stronger consistency when needed.

Explaining this nuance demonstrates an understanding of how ZooKeeper balances performance and correctness.

Client session semantics

ZooKeeper maintains client sessions that track connection state and ordering guarantees. Session semantics ensure that ephemeral znodes are cleaned up correctly and that client requests are processed in FIFO order.

Interviewers often appreciate candidates who connect session semantics back to coordination correctness.

Watches, notifications, and coordination patterns

ZooKeeper enables coordination through a notification mechanism called watches. Watches allow clients to be notified when specific znodes change, but they are intentionally designed as one-time triggers rather than continuous subscriptions. This design keeps the system simple and prevents the server from maintaining an unbounded notification state for every client.

In interviews, it is important to explain that watches are a performance and correctness trade-off. They provide timely hints about state changes without becoming a source of truth themselves.

How watches work in practice

A client sets a watch when reading a znode or listing its children. When the watched event occurs, ZooKeeper sends a notification to the client and clears the watch. The client must then re-read the state and set a new watch if needed.

This pattern ensures that clients always revalidate the state rather than relying on potentially stale notifications. Interviewers often look for this detail to confirm that candidates understand why watches are not reliable event streams.

Enabling coordination patterns with watches

ZooKeeper’s watches, combined with ephemeral and sequential znodes, enable common coordination patterns. Leader election relies on clients watching the smallest sequential znode. Distributed locks are implemented by watching predecessor nodes. Configuration management uses watches to notify services of updates.

In interviews, explaining how these patterns emerge from simple primitives demonstrates strong abstraction skills.

State management, durability, and snapshots

ZooKeeper stores the coordination state that other systems depend on for correctness. Losing a committed state can cause split-brain behavior, duplicate leaders, or inconsistent configuration. As a result, ZooKeeper treats durability as a core requirement rather than an optimization.

Interviewers expect candidates to understand that coordination systems must prioritize correctness even at the cost of performance.

Transaction logs and write-ahead logging

Every ZooKeeper server maintains a write-ahead transaction log. Before acknowledging a proposal, a server persists it to disk. This ensures that once a transaction is committed, it will survive crashes and restarts.

Explaining the role of write-ahead logging shows familiarity with durability techniques used in distributed systems.

Snapshots and state recovery

Over time, transaction logs grow large. ZooKeeper periodically creates snapshots of its in-memory state. These snapshots allow servers to recover quickly by loading a snapshot and replaying only recent transactions.

In interviews, describing snapshotting as a performance optimization layered on top of durability guarantees helps demonstrate a nuanced understanding.

Crash recovery behavior

When a server crashes and restarts, it loads the latest snapshot and replays committed transactions from the log. During the leader election, servers exchange state information to ensure that no committed transactions are lost.

This recovery flow reinforces ZooKeeper’s guarantee that the committed state is never rolled back.

Failure handling and fault tolerance

ZooKeeper assumes a crash-stop failure model. Servers may fail or become unreachable, but they do not behave maliciously. This assumption simplifies protocol design and is standard for many coordination systems.

Interviewers often test whether candidates mistakenly assume Byzantine fault tolerance.

Handling server failures

ZooKeeper tolerates failures as long as a quorum of servers remains available. If a follower fails, the system continues operating normally. If the leader fails, the cluster pauses writes and triggers a leader election.

Explaining that ZooKeeper prefers temporary unavailability over inconsistency demonstrates understanding of its design philosophy.

Network partitions and quorum behavior

During network partitions, ZooKeeper ensures that only the partition containing a quorum can make progress. Minority partitions become read-only or unavailable. This prevents split-brain scenarios where multiple leaders could emerge.

In interviews, explicitly tying quorum behavior to consistency guarantees is critical.

Slow nodes and performance isolation

Slow or overloaded nodes can degrade cluster performance. ZooKeeper mitigates this by requiring acknowledgments from a quorum rather than all nodes. Slow followers can be removed or isolated without compromising correctness.

This shows how ZooKeeper balances fault tolerance with practical performance considerations.

Consistency model and guarantees

ZooKeeper guarantees that all write operations are linearizable. This means that writes appear to occur atomically and in a single global order. All servers apply committed transactions in exactly the same sequence.

In interviews, this guarantee is often the most important point to articulate clearly.

Client session guarantees

ZooKeeper provides session-level guarantees that simplify client logic. Requests from a single client are processed in FIFO order. Clients also receive notifications about session expiration, allowing them to detect failures reliably.

Explaining session guarantees helps connect protocol behavior to application-level correctness.

Read consistency nuances

ZooKeeper does not guarantee that all reads see the most recent write unless the client explicitly synchronizes. Reads served by followers may lag behind the leader. Clients that require strong consistency must use synchronization primitives.

This nuanced explanation often differentiates strong candidates from those with superficial knowledge.

What ZooKeeper does not guarantee

ZooKeeper does not guarantee high availability during partitions, high write throughput, or complex query capabilities. It is optimized for coordination, not data storage or analytics.

Clearly stating limitations reinforces credibility in interviews.

Scaling ZooKeeper

ZooKeeper scales reads well because they can be served by any server in the cluster. Adding more followers or observers increases read capacity without affecting write quorum size.

Interviewers often expect candidates to mention observers as a read-scaling mechanism.

Write scalability limits

All writes go through the leader and require quorum acknowledgment. This makes write throughput inherently limited. ZooKeeper is not designed for workloads with frequent writes or large payloads.

In interviews, acknowledging this limitation shows realistic system understanding.

Cluster size constraints

ZooKeeper clusters are intentionally kept small. Increasing cluster size increases coordination overhead and latency for writes. Most production deployments use three to five servers.

Explaining why larger clusters do not improve throughput demonstrates sound performance reasoning.

Operational scaling considerations

As usage grows, operational complexity becomes a bottleneck. Monitoring, disk performance, and network stability become critical. ZooKeeper requires careful operational discipline to remain reliable at scale.

Interviewers often appreciate candidates who recognize that scaling is not just a theoretical concern but an operational one.

Security, access control, and isolation

ZooKeeper often sits at the core of distributed systems and controls leadership, configuration, and cluster membership. A security breach in ZooKeeper can cascade across multiple dependent systems. Because of this, ZooKeeper treats security as a first-class concern rather than an afterthought.

In interviews, acknowledging the sensitivity of coordination data signals that you understand ZooKeeper’s role as critical infrastructure.

Authentication mechanisms

ZooKeeper supports multiple authentication mechanisms to verify client identity. Clients authenticate using schemes such as digest-based authentication, Kerberos, or certificate-based mechanisms. Authentication establishes who the client is, but does not define what the client can do.

Explaining the separation between authentication and authorization shows clarity in security design.

Authorization and access control lists

ZooKeeper enforces authorization using access control lists attached to znodes. ACLs define which identities can read, write, create, or delete specific znodes. This allows fine-grained control over the coordination state and prevents accidental or malicious interference between applications.

In interviews, it is important to emphasize that ACLs help isolate multiple systems sharing the same ZooKeeper ensemble.

Multi-tenant isolation considerations

ZooKeeper is often shared by multiple applications. Namespace isolation and ACLs prevent one application from affecting another. However, poor isolation practices can still lead to noisy-neighbor problems.

Recognizing these risks demonstrates operational awareness beyond protocol-level understanding.

Trade-offs, limitations, and real-world constraints

ZooKeeper explicitly prioritizes consistency over availability. During network partitions or leader failures, the system may become unavailable for writes rather than risking a divergent state. This decision aligns with ZooKeeper’s role as a coordination system where an incorrect state is more dangerous than temporary unavailability.

In interviews, explicitly connecting this behavior to the CAP theorem strengthens your answer.

Performance and throughput limitations

ZooKeeper’s leader-based write path limits write throughput and increases latency under heavy load. This is an intentional design choice to preserve ordering and correctness. ZooKeeper is not suitable for workloads with frequent updates or large data payloads.

Interviewers often test whether candidates understand why ZooKeeper should not be used as a general-purpose datastore.

Operational complexity

Operating ZooKeeper reliably requires careful attention to disk performance, network latency, and monitoring. Misconfigured timeouts, slow disks, or overloaded leaders can destabilize the cluster. Operational discipline is often a bigger challenge than architectural design.

Acknowledging operational complexity demonstrates practical experience.

Common misuse patterns

ZooKeeper is sometimes misused as a message queue, a configuration database for large payloads, or a coordination system for high-frequency writes. These misuse patterns lead to performance degradation and instability.

In interviews, calling out misuse scenarios reinforces credibility and depth of understanding.

How to present ZooKeeper System Design in interviews

ZooKeeper System Design questions can easily consume an entire interview if not structured carefully. Strong candidates begin by clearly stating ZooKeeper’s purpose and guarantees, then progressively dive into architecture, consensus, and failure handling.

Interviewers value clarity and structure over exhaustive detail.

Prioritizing correctness and guarantees

In most interviews, guarantees matter more than protocol mechanics. Explaining linearizable writes, quorum-based decisions, and failure behavior is more important than detailing message formats or exact state transitions.

Demonstrating that you know where to stop is a sign of seniority.

Adapting depth based on interviewer signals

If the interviewer probes deeper into consensus, be prepared to explain ZAB at a conceptual level. If they focus on operational concerns, they shift toward scaling, monitoring, and failure recovery. Flexibility in depth shows strong communication skills.

Interviewers often assess not just knowledge, but how well you adapt explanations to the audience.

Common pitfalls to avoid

Candidates often fail by treating ZooKeeper as a database, ignoring failure scenarios, or overemphasizing performance optimizations. Avoiding these mistakes and focusing on correctness and coordination helps answers stand out.

Using structured prep resources effectively

Use Grokking the System Design Interview on Educative to learn curated patterns and practice full System Design problems step by step. It’s one of the most effective resources for building repeatable System Design intuition.

You can also choose the best System Design study material based on your experience:

Final thoughts

ZooKeeper represents one of the purest examples of distributed systems design in practice. It exists not to store data efficiently, but to enforce correctness across unreliable systems. Interviewers use ZooKeeper questions to assess whether candidates truly understand consensus, coordination, and failure handling.

Strong answers focus on guarantees first, architecture second, and trade-offs throughout. If you clearly explain why ZooKeeper makes its design choices and where its limitations lie, you demonstrate the level of reasoning expected from engineers who build and operate large-scale distributed systems.

Confidence, structure, and correctness matter more than memorizing protocols. If you anchor your explanation in these principles, ZooKeeper System Design becomes an opportunity to showcase deep systems thinking rather than an intimidating topic.